Lost in Translation

Yezdinar Village, Iraq

Dohuk is a welcoming place. After walking or taking taxis inside and around the city for two days, I covered enough ground and talked with enough people to see that while the welcome is clear for American, British, and other visitors, troublemakers can expect an entirely different greeting. People in Dohuk say they have no intentions of going back, or of carrying useless boulders from the past as they move forward.

After being in a war zone for nearly half a year, a few days in Dohuk becomes a chance to reconnect with civilized society, bustling with a people in hurried pursuit of progress. Seeing a little girl tucked away in a corner of her family's stall in the marketplace, absorbed in a book she’s reading about the solar system, it's easy to peek over her shoulder and peer into her imagination, and see it take her into space as Iraq's first astronaut. In her young life, never having known the fiery cage of war, the possibilities are still limitless.

I had been hearing about the Yezidi people who live in villages near Dohuk. Followers of an ancient religion, whose proponents claim it is the oldest in the world, there are thought to be about a half million Yezidis, living mostly in the area of Mosul, with smaller bands in forgotten villages scattered across Northern Iraq, Syria, Turkey and other lands. Saddam had labeled the Yezidis "Devil Worshippers," a claim I'd heard other Iraqis make, but no source offered substantiation. I wanted to know more.

Nearly everything I heard pronounced as fact about Yezidis was certain in only one narrow sense: before long, someone equally confident of their information would provide a different set of facts. The only way to find the truth would be to talk with Yezidis in situ, so I asked an interpreter in Dohuk to take me to a Yezidi village.

This wasn't my first foray in search of mythic danger. I'd learned some things from when I tracked down cannibals in the jungles of northern India. A current anthropological rap sheet is of paramount necessity before venturing alone into the wild. Safety first is my motto.

"Of course not!" he answered immediately, incredulous at the very idea. "They are Yezidi! They are good people."

"Just asking." I said, thinking safety first.

The road from Dohuk

The village of Yezdinar is about twenty miles outside of Dohuk, and on the way I reflected on what I knew of the religion.

Some believe Yezidism is over 5,000 years old, while others claim thousands of years older. Nobody seems to know. The Yezidis have their own fuzziness on dates, and for the Yezidis it seems enough to say that theirs is the oldest religion in the world. The Hindus of India make the same claim about their religion, while others in Nepal and Tibet make calendar claims of their own. One might intuit such proclamations as offering evidence of the essential truth of a religion—having withstood the test of time, it must be the order of things. Some see age as the proof of the rightness of one path over others, implying that precedence is precedence, like when a Muslim man in Kashmir once said to me, as if it would explain everything, "Ahhhh, the Sikhs, they are just a young religion."

Some tenets of Yezidism are readily understandable to westerners: Yezidis worship one God but no prophets. They recognize and respect both Jesus and Mohammed, but as men of faith, not prophets. Where the doctrine starts to become hazy is when the angels appear.

An older Yezidi man with whom I speak on occasion says there are seven angels: Izrafael, Jibrael, Michael, Nordael, Dardael, Shamnael, and Azazael. All were gathered at a heavenly meeting when God told them they should bow to none other than Him. This arrangement worked for a span of forty thousand years, until God created Adam by mixing the "elements": earth, air, water and fire. When God told the seven angels to bow before Adam, six complied. A seventh angel, citing God's order that the angels bow only to God, refused. Although this angel was God's favorite, his disobedience cast him from grace.

There is some dispute among Yezidis about the identity of the seventh angel; some believe it was Jibrael, while others believe it was Izrafael. Much seems lost to time. But whatever his former name, when this seventh Angel, most beloved of God, fell from grace, he was the most powerful angel in Heaven and on Earth. He rose as the Archangel Malak Ta'us. (Although this, too, is the subject of some debate; some Yezidis call him Ta’us Malak.) His herald is the peacock, for it is "by far the most beautiful bird in the world," and the name, Malak Ta'us, literally means, "King of Peacocks."

Most Yezidis equate Malak Ta'us with Satan, a mainstay in many religions but otherwise not mentioned in Yezidism. Some Yezidis claim that Malak Ta'us is like a god himself, at least in terms of his power--particularly over the fortunes of the descendents of Adam. In this religion, God created Adam, but no Eve, and therefore all men came from Adam alone. The Yezidis were first born among all men, and consider themselves to be "the chosen people."

Malak Ta'us descended from Heaven to Earth on a Wednesday to tell man that he is the Archangel, making this a day for religious observation. The Yezidis mark the day by not bathing on Wednesday evenings. They believe their dead must wash, and for this they need water; the dead wash on the holy day of Wednesday.

Never on Wednesday: Laundry Day in Yezdinar

Not only do shards of Judeo-Christianity glint in this amalgam, but a close look also reveals pieces of Hinduism, especially in the prominence of castes. There are five Yezidi castes--depending on who one asks--the "most important" being the Pir, then Shaikh, Kawal, Murabby, and finally the Mureed (the follower). Descriptions of the Mureed are similar to the Dalits of Hinduism. The Yezidis are strictly forbidden to marry outside the Yezidi, and must marry within their caste.

Yezidis have two holy books: the Book of Revelation and the Black Book. The old Yezidi man informed me that although the Black Book is kept secret so it cannot be defamed, he would like to translate it into English. The title apparently has been rendered.

While Kurds say the Yezidis are Kurds, the Yezidis claim to be neither Arab nor Kurd, simply Yezidis or, perhaps, Yezidi first and Kurd second. In a fashion similar to how the word "Jewish" is used, the designation "Yezidi" applies to both a set of religious beliefs and a genetic or tribal identity. Because Yezidis keep to themselves, it is easy for others to misunderstand, or deliberately mis-project, the Yezidi religion. This can have dire consequences.

The most recent example was when Saddam Hussein labeled the Yezidis "Devil Worshippers," which he justified by equating Malak Ta'us with Satan. This was no minor misunderstanding, nor was it just a rhetorical flourish, but a deliberate attempt to exploit the reservoir of suspicion that encircles enclaves of people who keep to themselves, and in this case to cleave the Yezidis from the Kurds.

Exacerbating matters was that the Yezidi religion is such an amalgam of beliefs and practices. History, more so than theology, provides a key to this code. When a Yezidi holy man asserted that Yezidis all love Jesus, too, it lent credence to other reports I'd heard that Yezidism conflated with religions such as Islam, Christianity, Judaism, and even Zoroastrianism over the centuries, as the Yezidi came into contact with the followers of these religions.

Even without an authoritative timeline showing when these mergers occurred, the mixing of diverse dogma and symbolism in Yezidism does not flow logically or track a linear course of thinking. It goes far beyond the bounds of any off-the-shelf syncretism, and stands as testament for the ability of the Yezidis to dissimulate in the face of destruction to preserve the body. Rather than cast off their beliefs in subjugation to conquerors, they instead incorporated elements of the dominant belief system into their amalgam, using their cultural and racial identity as Yezidi for the mortar. They built their faith, and their villages, with this concrete; its ability to withstand the destructive forces of outside elements would have a severe test in recent times.

Saddam Hussein's hatred for Yezidis and Kurds was matched only by his desire to eradicate every last one of them from Iraq. Even though most Kurds are actually Sunni Muslims, as is the now imprisoned dictator, his hatred for them remained unabated, and was relentless. Hussein knew that a collision of religious beliefs carved fault lines between the Yezidis and the Kurds who surround them. He used his common point of reference with the Kurds to sharpen their divide from the Yezidis, by calling them "Devil Worshippers." But just because the Yezidis don't have a Satan figure in their holy book, doesn't mean they can't spot a devil when they see one. Together with the Kurds, they resisted Hussein's will. Today, while the real peacock sits in jail, the unvanquished Yezidis are rebuilding their homeland.

Homes in the Yezdinar Village

The Village

The sun approached apex above clear skies, warming and drying the air as we entered the Yezdinar village. Several Yezidi men welcomed me graciously, and though my interpreter was Sunni Muslim, they welcomed him, too. None of the men had ever met an American.

The Headman invited me into his home, where small children darted here and about, clearly excited yet smiling shyly at the foreigner in strange clothes. The men took off their shoes and as I started to unlace my boots, the Headman motioned that I could leave them on. I recognized this as an honor, but smiled and removed my battered boots before following them into a rectangular room. Pillows cushioning the floor and propped up against the walls were the only furniture, but at one end of the room a television flickered silently while an air conditioner hummed steadily at the other.

There were six men in the room, all sitting cross-legged. Four Yezidi men sat along the wall across from me, the Headman smoked a home-rolled cigarette.

My interpreter sat to my left, and we began with customary civilities:

"You are my honored guest," said the Headman, who told me his name was Mr. Qatou Samou Haji Aldanani.

The conversation thus launched, we meandered across tenses and back again as we talked about the village and the forces that had shaped its fortunes.

Mr Qatou said there were twenty families in the village, some with nine or ten children; while some men in Yezdinar have up to five wives, others keep only one. They had sheep, cows and ducks, he said, though I hadn't seen a pond.

The village had come back strong after being destroyed by Saddam in 1978. The people were completely unhinged, Mr. Qatou said, when Saddam's Army bombed the village flat, then came and stole absolutely everything; sheep, cows, ducks, everything. Even a dog.

"Yes."

"And they took the dog?" Silence expressed the residue of disgust.

Mr. Qatou described how Saddam's army grabbed two men, each twenty years old, shot them, and then forced the families pay for the bullets.

At times throughout our conversation, the chronologies loosened and grew confusing. I remain unsure about whether the men were killed during that same attack, or at some other time. But it seemed both impolitic and impolite to try to pin down the date when the mention of the memory cast a shadow over our thoughts.

I wanted to know more about Mr. Qatou's life. He said he was born in 1949, and after being drafted into the Army, was sent to fight the Iranians for 7 years before being captured and imprisoned in Iran for 10 years. When it came to time sequences, I questioned the competence of my interpreter, for the numbers and years never seemed to completely adhere to history; and though the interpreter was kind, he was less than fastidious. His English wasn't entirely fluent.

Sensing the congestion this confusion was having on our conversation, Mr. Qatou rose, exited the room, and returned with a document, from the International Red Cross, confirming that he was born in 1949; had been captured by Iranian forces in 1982; and then repatriated to Iraq in September 1990.

Iraq invaded Kuwait in August of 1990. When the US announced that the invasion would not stand, Iran released the Iraqi prisoners of war. This meant that Mr. Qatou had come home just in time for another war. His life was defined by war: drafted to fight Iran; captured by Iran; released after years only as fodder for the Americans, and today, I being the first American he met, sitting with him in his home, trying to sort the tangle of dates and facts.

What is certain is that during this second war of Mr. Qatou's life (the "Gulf War" for the first Coalition), the Kurds received support from US Special Forces and others. Sent to bolster Peshmerga strength, they distracted Saddam's army in the north, while the Coalition expelled Iraq from Kuwait in the south.

Iraq's army accordioned in defeat, and the first Coalition folded most of their tents and sailed home, leaving the Kurds to fend for themselves. Saddam had revenge on his breath when he turned his attention north and unsheathed his fury against the Kurds. Initially a slaughter of wholesale proportions, somehow, still the Kurds kept fighting. They hung on until the US gave military support and maintained the no-fly zone overhead. In 1993, Mr. Qatou was able to return to the rubble that had once been Yezdinar.

An Iraqi. A Kurd. A Yezidi. A village Headman. Whatever the label, more than forty years after his birth, this man came home. Only now, after the latest war, does Mr. Qatou finally have confidence in the peace, after more than a half century of life lived under orders or under sentence.

This seemed like the moment to ask the question, "What do you think of the United States?"

"We cry when America loses one soldier. We pray for the soldiers every night."

Many Kurds had expressed the same sentiment. One had said poetically: "For every drop of American blood, we shed one thousand Kurdish tears."

"Also very good."

His answer for some of the other countries, those that abandoned his people to get back to their beer and wine, was merely a quick frown followed by silence.

Ever the gracious host, Mr. Qatou asked me if I was hungry, and if I would share a meal with him.

My enthusiastic acceptance evoked hearty laughter from the other five men, who spoke among themselves in Kurdish.

"Why is everyone laughing?" I asked.

"We thought you to say 'no,'" Mr. Qatou replied.

"I am very hungry," I said, my enthusiasm not waning in the least. "I would definitely like to eat!"

And they laughed again, and Mr. Qatou suggested we tour his village while his wife prepared our meals.

"As you wish," I said, and we all rose and began walking out. I stopped to put my boots on, their bad condition seeming somehow more obvious to me.

New Roof for the Sheep Pen

We started our walk around the village, our conversation covering more ground than our feet.

"What do you mean?" asked Mr. Qatou.

"Security problems?"

"Is very safe."

"Problems with running the village?"

"Water is our only problem. Our well is a problem. Otherwise, all is good."

"May we look at your well?" I asked.

"That's deep."

"Yes."

I asked to see the water run, and as water came from the hose, I coaxed my fatigued Nikon to photograph him, but having gone the way of the boots, the camera is mostly broken, so it took several attempts to photograph the scene. Once I got a decent photo, the men replaced the cover and we headed to the village school.

Mr. Qatou demonstrating the town water supply

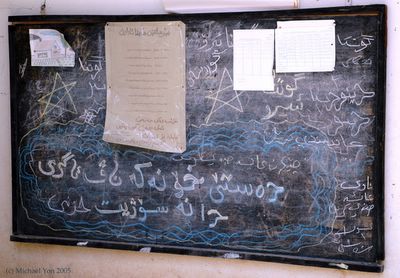

About 70 children attend classes in grades one through six. Mr. Qatou called to the school headmaster who lived next door, and he took us into the school courtyard. I noticed a chalkboard with something written in Kurdish on the bottom in Arabic characters. According to the interpreter, it must have been written by a child, and it read: Don't put your hand in fire. If you put your hand in fire your hand will burn and you will cry. Mr. Qatou explained that kids had to be taught about fire in the village. When I told him that American kids burn down houses every day as a result of playing with matches, he seemed genuinely surprised.

Blackboard in Yezdinar Village school

We left the school and continued strolling through the village, with Mr. Qatou pointing out the landmarks that one would expect in a village that had been nearly decimated by war. He showed me where the young men had been shot, and we ambled around heaps of rubble that had been buildings before Saddam's army came rampaging. Something made me think of recent scandalous headlines, and I asked:

"Yes." Mr. Qatou said.

"Many people were angry by the photos," I said.

"Why would they be angry?"

"What did the Iraqi people think when they saw him with no clothes?"

"He was a bad man."

"Do you want him to be executed? To be killed?"

"I want him to stay in jail."

We found ourselves in front of his house. Once we removed our shoes and boots, we walked inside and sat on the cushions. His wife delivered roasted duck and vegetables, and I ate more than my share. The meal was delicious. My appetite and appreciation for his wife's skill in the kitchen filled him with pride the way that duck filled my stomach. It was a most pleasant meal.

His grandchildren gathered around him, peeking at me from behind his weathered arms. He seemed unaware of the slight smile that eased across his face whenever he looked at the children. They constantly sought his approval for each small gesture of interaction with this stranger in their grandfather's home, which he granted with slight nods.

"My children's children are free...it was worth it."

The demands of digestion had quieted my questioning, but he still wanted to talk, so I listened intently. Although I had only known him for a few short hours, it was clear that Mr. Qatou liked to talk about the future.

"Yes," I said. "It was worth it, no?"

"What?" he asked, confused at my meaning.

"Your struggle," I said. "Now you are free."

In a Child's Eyes: Happiness Under a Rainbow Umbrella. A Yezidi-Kurdish-Iraqi Schoolgirl's Drawing Shows Her Imagination of the World

[Please add your name to the free emailing list for notification of new Dispatches.]

<< Home